Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts and the Chicago Council of Lawyers are excited to release our new report, One Size Doesn’t Fit All: A Review of Post-Plea Problem-Solving Courts in Cook County. In it, we offer a holistic picture of the scope of specialty (or “problem-solving”) courts, which have become an increasingly popular tool for lowering the number of people in prisons in the United States. There were three post-plea problem-solving courts in Cook County in 2011; as of February 2023, we have 21. Despite their popularity, the program models, processes, functions, and efficacy of problem-solving courts remain largely unmonitored and understudied.

The full report can be found below; for a summary, click here.

What problems are these courts trying to solve?

Problem-solving courts (PSCs) vary across jurisdictions, but the most common focus is on people whose contact with the legal system relates someway to drugs, intimate partner violence, diagnosed mental illnesses, or being a U.S. Military Veteran.

This report focuses on Cook County’s “post-plea” diversion courts. Post-plea specialty courts require that the accused person plead guilty to allegations, but gives them a chance to complete a sentence of probation instead of imprisonment. If they successfully complete the supervision term, the PSC judge can vacate the person’s conviction. In theory, post-plea specialty courts are alternatives to the traditional criminal court system, which is often inflexible to individuals legally deemed guilty or in violation of criminal law.

How do Cook County’s problem-solving courts perform?

The Cook County Circuit Court has 21 post-plea problem-solving courtrooms through various branches: seven Mental Health Courts (MHCs), eight Drug Treatment Courts (DTCs), including the Access to Treatment (ACT) Court, and six Veterans Treatment Courts (VTCs). Our report includes data collected by court-watching volunteers in DTCs and MHCs: In total, our court-watchers observed a total of 51 problem-solving court participants and seven judges across five of Cook County’s municipal districts (Chicago, Skokie, Maywood, Rolling Meadows, and Bridgeview) between March 17 to May 27, 2022.

This report demonstrates the various challenges that influence the reality of the Cook County problem-solving courts, faced both by the courts themselves and their participants. Among our key findings, we demonstrate:

- White people are about twice as prevalent in problem-solving courts as they are overall in the felony courts. Except for the ACT Court (which has a more disproportionately Black demographic), all PSCs have a higher proportion of White participants than the demographics of people involved in Cook County’s criminal legal system generally.

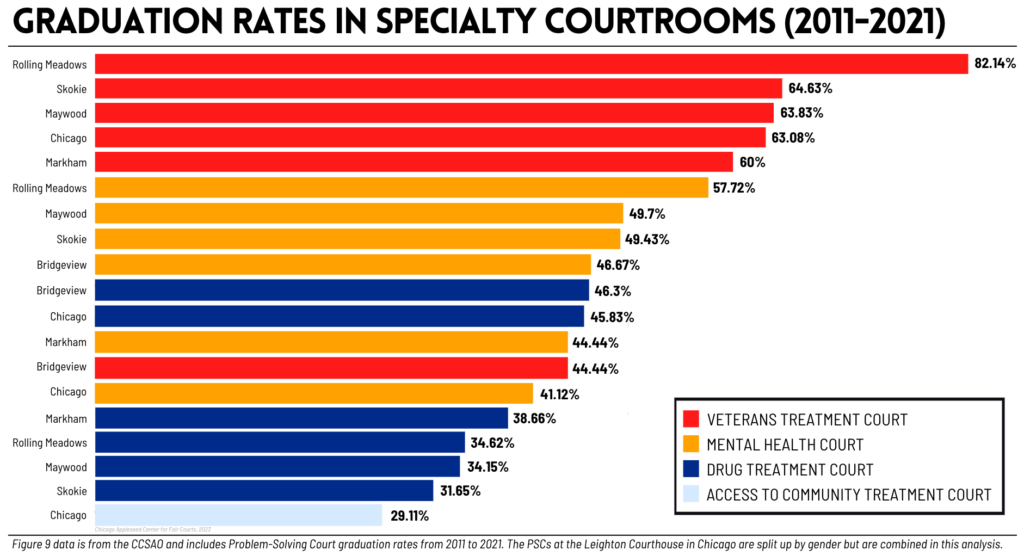

- The combined graduation rate in Cook County’s post-plea problem-solving courtrooms is 55%, but there are wide variations in graduation rates between individual courtrooms. Only the Veterans Treatment Courts have an overall graduation rate above half (61%); the Mental Health Courts have an overall graduation rate of 47% and the Drug Treatment Courts have a graduation rate of 42% (with ACT Court having a graduation rate of 29%). There is wide variation in graduation rates between individual courtrooms, which suggests that judges’ individual practices influence participants’ success. The impact of a judge’s own “style” and discretion create different circumstances for each court participant. Speaking programmatically, there was collective confusion among those we interviewed regarding the design of the program and how rewards and sanctions were administered to participants. Consequences can vary widely, ranging from homework assignments to incarceration.

- All the PSC programs are intended to be two years in length; at least 20% of PSC graduates and 12% of people who failed the programs spent more than 2 years on probation. Data showed that, on average, participants are spending up to 120 days in pretrial incarceration before they formally enroll in a problem-solving court. Although the data does not show how many PSC participants are ultimately punished with jail time during or after their time in a program, statute allows the court to sanction participants with incarceration for up to 180 days.

More research is needed to better understand the effect of diversion and problem-solving courts on participants’ lives and legal system outcomes, but it is clear that many of the requirements in problem-solving courts are unrealistic, burdensome, and counterproductive (the main driver of a participant’s incarceration is as punishment for breaking program rules). Put simply, Cook County’s problem-solving courts help many people but harm others.

What’s next?

Problem-solving courts can provide people resources they may not have had access to otherwise, but some of the parameters present act as barriers to participants. Frequent, random mandatory drug testing, for example, harms people who may not have access to childcare, transportation, or the ability to take time off of work or school. These requirements can exacerbate participants’ mental health issues such as anxiety and depression.

Above all else, achieving positive outcomes for more people in the future will require less punitive and more restorative, treatment-oriented approaches. The policy recommendations we provide in our report are based on the premises that:

- Incarceration should not be used as a sanction for people in the problem-solving courts. The demanding rules and abstinence-only ideology are counterproductive, as incarceration is most often used as a punishment for breaking these rules.

- All people deserve autonomy and should have the right to determine their goals for and methods of treatment.

- Accessible, community-based resources are essential to successful treatment and legal system outcomes.

Cook County’s problem-solving courts have clearly helped some people who succeed and thrive in these programs, but data is showing that many of these courts are seeing diminishing returns. There are ways to improve these courts to better serve the people who move through these courts and their communities. It is important that the courts reevaluate policies, practices, and renew their focus on evidence-based treatment models. Illinois Public Act 102-1041, which took effect in June of 2022, standardizes the treatment court statutes, ensures individuals with similar needs have access to necessary resources, and further promotes best practices. This report examined the state of Cook County’s problem-solving courts prior to the new law, but we are hopeful for improvements in light of the passage of the Act.