Waiting for Justice: An examination of the Cook County Criminal Court backlog in the age of COVID-19

The content in this article was originally submitted as testimony to the Cook County Board of Commissioners’ Criminal Justice Committee meeting on January 27, 2020, about peoples’ lengths of stay in Cook County Jail and on electronic monitoring, and the effect COVID-19 has had on the growing jail population.

CORRECTION 1/29/21 – A previous version of this article had outdated information and incorrectly stated that 195 people had been in jail for six months on misdemeanor charges and another 56 on electronic monitoring (the correct numbers are 16 and 25, respectfully) and that 266 people in the jail and 365 on house arrest had served more than 6 months on Class 4 felonies (the correct numbers are 100 in jail and 399 on EM).

Introduction

Cook County has one of the largest unified criminal court systems in the world, with a budget of over $275 million annually and more than 1 million cases filed each year. Combined with the budgets of the County Departments that support the courts (Law Office of the Public Defender, State’s Attorney’s Office, Sheriff’s Office, and other support services), Cook County taxpayers spend well over $1 billion on the administration of criminal justice every year.

The Cook County Jail (CCJ) is also the largest single-site jail in the country, with a population of approximately 5,000 residents daily – about 92% of whom are held in pretrial detention while presumed innocent. The Sheriff’s Electronic Monitoring (EM) Program also incarcerates people accused of crimes in ever increasing numbers: in 2020, the program averaged 3,200 people per day, and today currently stands at 3,669 people (a 38% increase since 2020).

These numbers are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to how many people are waiting for their cases to be resolved in and out of custody. People – both those accused and the victims of crime – are waiting increasingly long periods of time for justice, as COVID-19 has slowed court processing to a crawl.

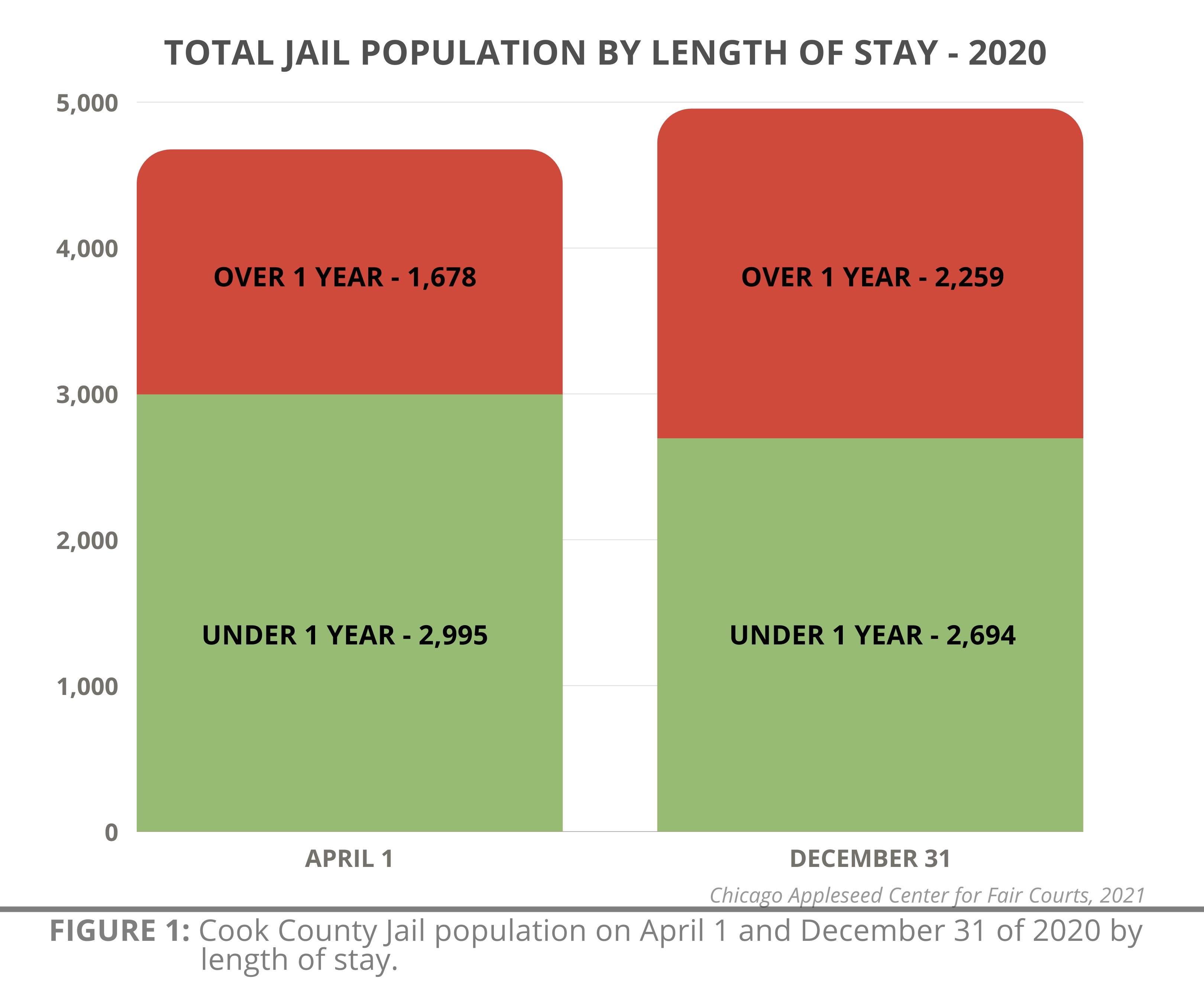

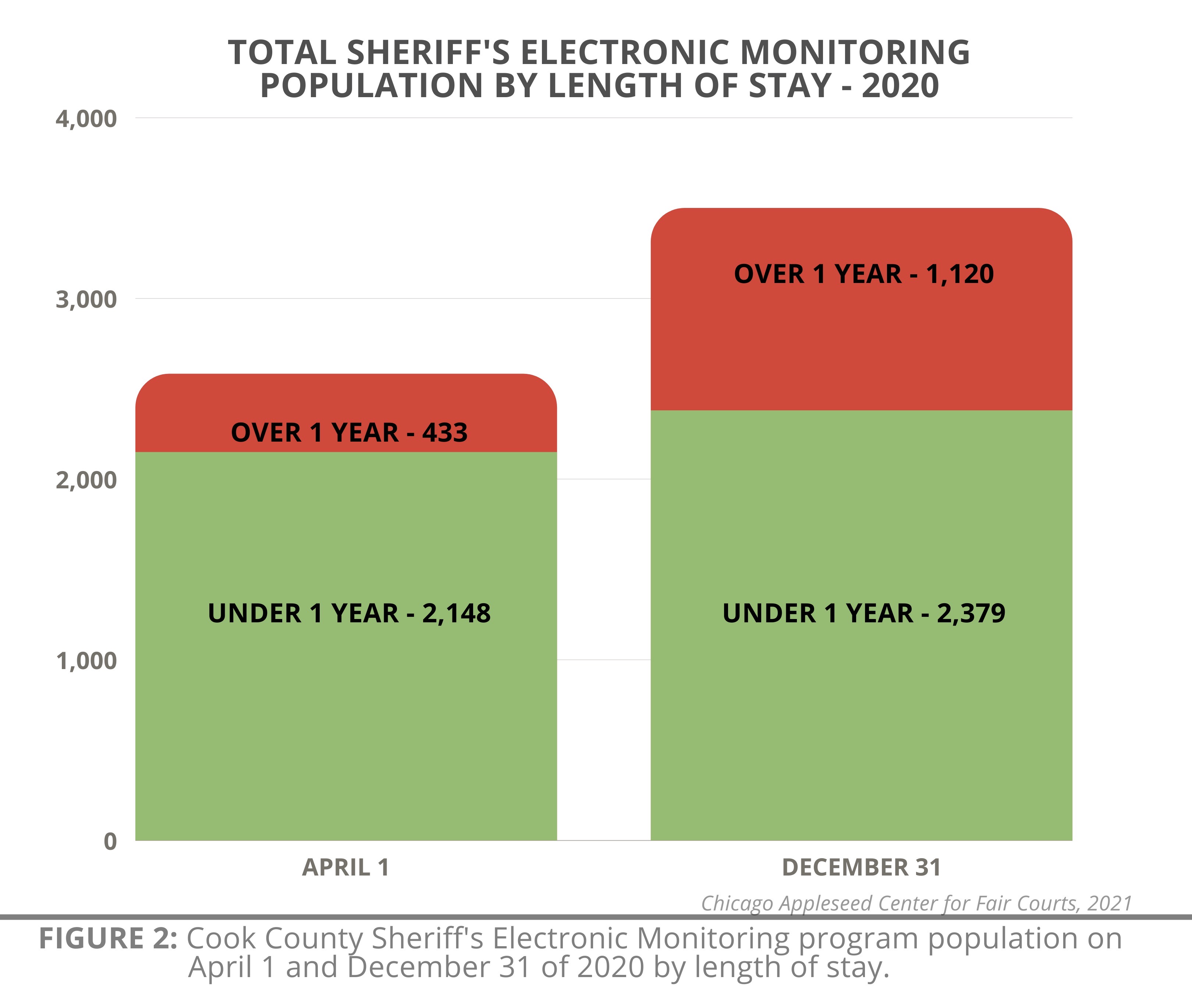

The most acute harm caused by these delays is experienced by people waiting in jail pretrial and those incarcerated by way of electronic monitoring in their homes. On April 1, 2020, at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in the Cook County Department of Corrections (CCDOC) system, the median length of time people spent in CCJ was about eight months. As of December 31, 2020, that median has risen to almost 11 months. On Electronic Monitoring, 32% of participants – 1,122 people – have been waiting on house arrest for their cases to be resolved for over one year without violating the terms of the program; about two-thirds of those people are awaiting for their day in court for non-forcible (or “non-violent”) felonies.There are myriad factors that contribute to these case delays. Some are new challenges posed by COVID-19, but most predate the pandemic, resulting from outdated court practices and either the inability or unwillingness to update pretrial processes. The National Center for State Courts’ (NCSC) “Model Time Standard for State Trial Courts” for felony case disposition is one year. While the NCSC recognizes that not every case is resolvable in that time period, most are – which is why their standard is that: 75% of cases should be resolved within 3 months, 90% within 6 months, and 98% within 1 year. In Cook County, on average between 2015 and 2020 (according to the State’s Attorney’s public data), just 28% of felony cases are resolved within 3 months; 47% in under 6 months; and 73% in under a year.

The Immediate Problem: Extreme Lengths of Stay In the Jail Due to COVID-19 Court Delays

Although Cook County has had a long standing problem of cases pending for long periods of time and causing lengthy jail stays, the current situation is particularly acute: COVID-19 has brought major court slowdowns. As a result, more and more people have been behind bars or under house arrest for over a year without having been proven guilty of any crime.

Early in the pandemic the jail population was at approximately the same level as it had been in previous years. In Spring of 2020, only 36% of pretrial jail inmates had been in custody for more than one year; as of December 31, that percentage is 46%.

The electronic monitoring program has even starker numbers. On April 1, 2020, only about 17% of people confined to their homes had been on house arrest for more than one year. Now, 32% of participants have waited over a year for their cases to be resolved. More disturbingly, the program has grown substantially, from a population of about 2,600 on April 1 to about 3,500 on December 31st – meaning that the absolute number of Cook County residents who have been on the program for more than one year has nearly tripled.

As of December 31, 2020, over 1,000 people in Cook County had been on house arrest for over one year, and over 2,200 have been in jail for over one year, while presumed innocent (awaiting trial).

Cook County’s efforts to reduce the jail population lags far behind some of its peer cities. Other cities have massively reduced their jail populations during the COVID-19 pandemic and kept that population low:

- San Francisco has successfully kept its jail population low during the pandemic, dropping 24% from a population of 1,006 in March to just 760 in December.

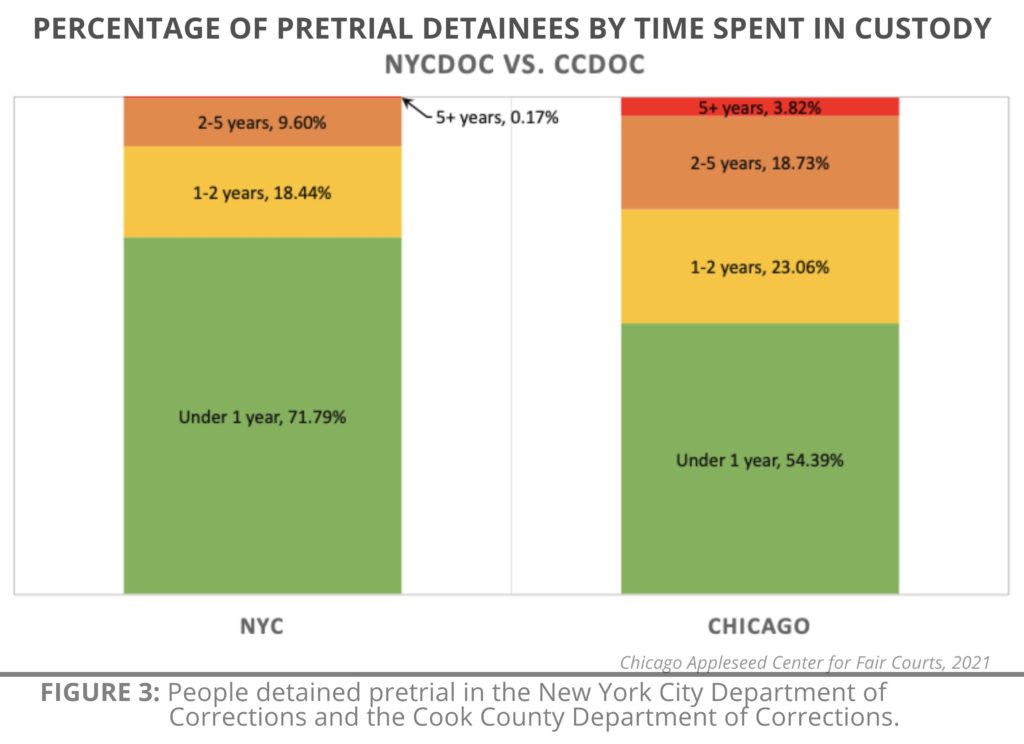

- New York City, like Chicago, has struggled to keep its jail population low as the pandemic has progressed [See Figure 3] – though it fell 30% between March 1and April 29, it has slowly returned to almost pre-pandemic levels. However, New York has kept people in its jail for less time during the pandemic: 72% of detainees in the NYC Department of Corrections had been in custody for less than a year; in Cook County, that number is 54%. New York also has almost no one who has been in custody for extremely long periods of time, while Cook County has over 100 people who have waited in custody pretrial for over five years.

Although Cook County lowered its jail population substantially in the early summer, it has now returned to above its population in April 2020, despite continued deaths of both detainees and staff from COVID-19, and, as noted above, lengths of stay continue to increase. This is not the case in some other large cities that have also been hard-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Why is this happening?

Fundamentally, there are two ways that an individual can leave the Cook County Jail: (1) a bail they can pay or conditions of pretrial release are set in their case, or (2) their case concluded by plea, dismissal, or trial. Right now, both of these mechanisms are moving extremely slowly due to the COVID-19 pandemic – but these problems are not new. The pandemic has exacerbated and highlighted inefficiencies and injustices in the Cook County Courts that have existed for decades, and made them all the more harmful to Cook County residents accused of crimes.

This report addresses these issues in turn, and provides recommendations for addressing each: Section I concerns COVID-19 related delays in case processing and case resolutions; Section II concerns the failure to appropriately and legally provide affordable bail and/or pre-trial release to many jail detainees; and Section III concerns long-standing administrative problems that make the Cook County Courts’ pretrial process move more slowly than other peer court systems.

II. People are Waiting in Custody Longer because Cook County is Vastly Behind Schedule in Resolving Felony Criminal Cases

In the Illinois criminal court system, there are three basic ways to resolve, or end, a case: (1) the defendant pleads guilty, (2) the prosecutor dismisses the case, or (3) the case is taken to trial and a judge or jury decides whether the person is or is not guilty. There are some other rare ways that cases can resolve. An individual could die while the case against them is pending. If a defendant is found to be unfit to stand trial, or pleads not guilty by reason of insanity, there are different civil commitment dispositions available. Lastly, a small number of cases are only disposed of after an appeal is made and the appellate court orders a certain outcome. Together, these scenarios account for only about 3% of total felony dispositions (about 1,643 cases) and are not included in this analysis.

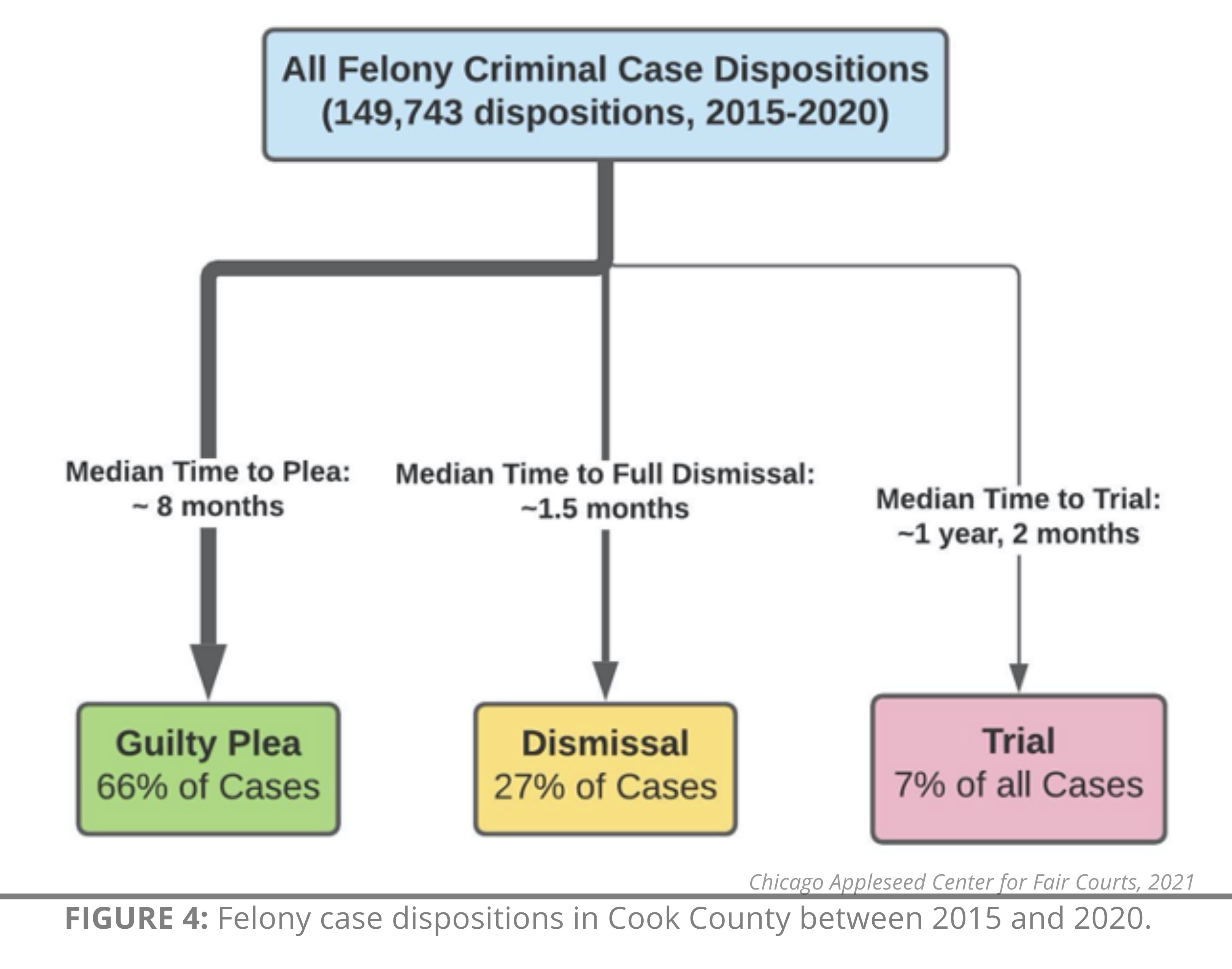

Cases can resolve in a number of ways. As shown in Figure 4, about two-thirds of cases, 66%, end in guilty pleas – either to the charge originally indicted by the prosecutor or to some lesser version of that charge, as part of the plea deal. A substantial portion of cases, 27%, are dismissed – usually because the prosecution chooses to dismiss them for lack of evidence or other reasons, or because the defendant completes a diversion program. Most dismissals occur within the first few months a case is pending, though a substantial number (14% of all dismissals – about 5,500 cases between 2015 and 2020) take place after a case has been pending for a year or more. Only about 7% of cases go to trial, and of those, the vast majority are “bench trials,” in which a judge (not a jury) decides the facts of the case. Jury trials are the rarest form of case resolution.

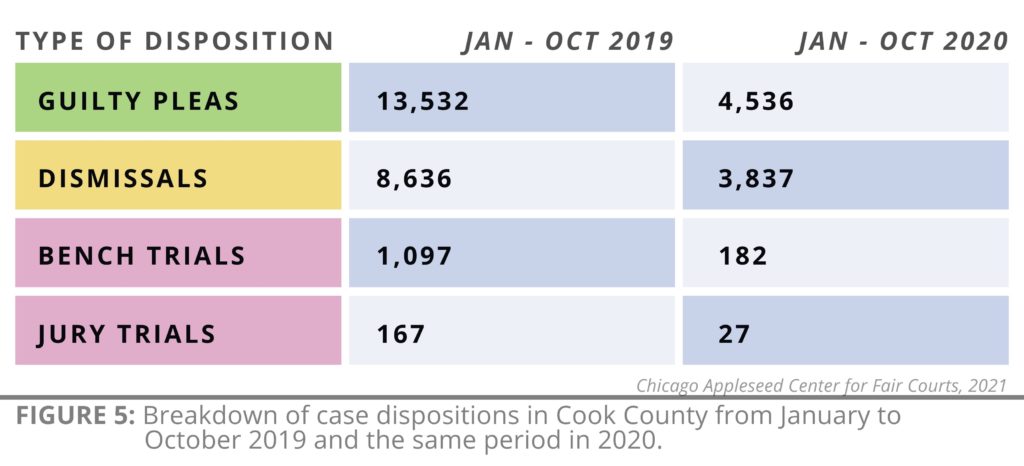

In 2020, the pandemic caused the courts to essentially shut down – but this, however warranted, has contributed significantly to the backlog of cases in the Cook County Criminal Court. In all categories of disposition for 2020, the Cook County Courts were significantly behind the numbers from 2019. Based on the State’s Attorney’s and Chicago Police Department’s arrest numbers from 2020, our estimate is that, currently, the Court’s total backlog has over 10,000 felony cases.

Arrests were very low during the early parts of the pandemic, but as the months progress, new felony arrests have risen faster than the courts process cases, making the case backlog – and the jail population – bigger and bigger. Still, arrests and new felony case initiations were lower in 2020 than in previous years, but most of the cases that are “due” to be disposed of predate the pandemic.

Because the court is moving more slowly in general, plea negotiations are also moving slower and many guilty pleas have not been entered. Defense attorneys also have limited access to their clients in the jail, for the sake of health during the pandemic, and pretrial detainees are usually not brought in-person to their court dates by the Sheriff’s Office. This means that many defense attorneys cannot even appropriately discuss plea offers with their clients. It is also harder for State’s Attorneys to contact crime victims to go over plea offers, due to the upheaval in many people’s lives during the pandemic.

Dismissals are low primarily because the mechanisms in the State’s Attorney’s Office that usually lead to cases being dismissed are not functioning as normal. When cases, particularly low-level felonies, lack sufficient evidence to warrant prosecution it is usually discovered in the first few months of the case – often at the preliminary hearing or indictment (first) stage. Under Illinois law, that preliminary hearing must happen within 30 days of arrest. However, State’s Attorneys have been filing – and judges have been granting – extension motions to delay these preliminary hearings because of apparent difficulties in speaking to witnesses and getting necessary police officers to appear in court. These motions are understandable, but have led to fewer cases being reviewed and dismissed soon after they are filed.

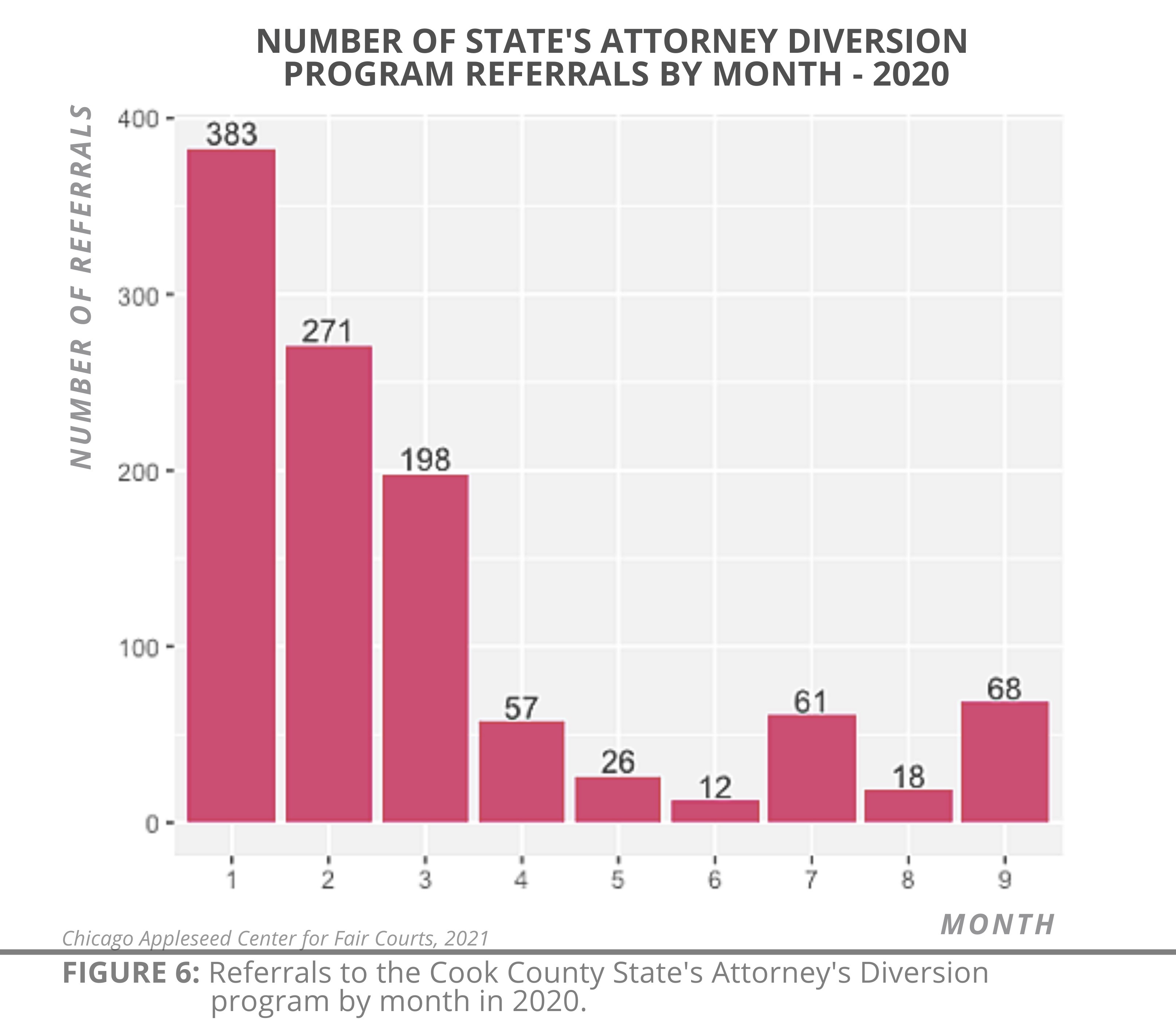

The State’s Attorney’s diversion programs require defendants to complete evaluations and some course of treatment/programming in order to dismiss low-level cases, but these processes have also ground to a halt [See Figure 6]. These programs are usually initiated by in-person interviews of defendants with court personnel, but since few defendants are being asked to appear in person for safety reasons, these interviews have not been able to progress as normal.

Trials and substantive pretrial motions have also largely stopped because of the obvious health risks of in-person trials. A trial requires evaluations of the credibility of witnesses and the persuasiveness of arguments; trials conducted through video are not, in most cases, effective in protecting people’s rights. Research shows that defendants have markedly worse outcomes in video-based hearings than in live ones. One 2010 study of bail hearings, for example, found video-teleconferenced hearings resulted in substantially higher bond amounts than in-person hearings – ranging anywhere from 50% to 90% higher, depending on alleged offense.

The Cook County Chief Judge, the Public Defender, and the State’s Attorney announced recently that in-person trials, including jury trials, will proceed starting in February. This is excellent progress; many jurisdictions around the country and around the state have successfully conducted safe, in-person court hearings with live witnesses. It is important to remember, however, that restarting trials will only address a small fraction of the people who are currently incarcerated at the jail, and an even smaller fraction of the overall criminal court case backlog.

For some jail detainees, resolution of their case is the only realistic way out of the jail. Until Cook County resumes a more normal speed of case resolutions, the average lengths of stay in the jail and on electronic monitoring can be expected to worsen.

Recommendations

Throughout 2020 and January 2021, Chicago Appleseed, the Chicago Council of Lawyers, and our community partner advocacy groups have proposed numerous methods for equitably reducing the jail population and shortening general length of stay. A few key steps would go a long way towards resolving this backlog:

- A centralized group of stakeholders must identify people in the jail whose cases are ready for agreed non-trial resolution and work to enter guilty pleas or dismiss cases as soon as possible. There has been some attempt to identify cases in need of plea or dismissal, and the Law Office of the Public Defender, the State’s Attorney’s Office, and Office of the Chief Judge have all directed their staff to prioritize these cases. Unfortunately, though, this case backlog cannot be resolved incrementally in each of the dozens of courtrooms in five courthouses throughout the county. In ‘normal’ times, the court system is wise to make sure that judges, State’s Attorneys, and Public Defenders keep personal control over individual cases from start to finish, but these are not normal times. There have been consistent problems throughout the pandemic with individual judges’ applying different rules in their courtrooms – about everything from case management to whether defendants and their attorneys need to appear in court in-person for certain court dates. Similarly, defense attorneys have reported to Chicago Appleseed about individual State’s Attorneys varying widely in their willingness to give reasonable plea offers and their quickness in resolving cases. A centralized group of stakeholders given the express purpose to reduce the jail population and the case backlog must be convened and given power to make decisions about cases, and they must have a central, efficient court call to get necessary agreed dispositions filed. All stakeholders must collaborate on this goal in order for it to be successful, including the Sheriff, who must provide efficient and reliable transportation of defendants for court dates where they need to appear in-person.

- Stakeholders should prioritize agreed plea resolutions that will likely result in probation or an immediate release onto parole. As court cases linger for longer periods, a larger number of detainees have already served so much time pretrial that they will have little-to-no time left to serve if convicted and sentenced to jail time. Still more people will never see post-conviction jail or prison time at all, since they are eligible for probation. There are 16 people in Cook County Jail who have been in custody for longer than six months on misdemeanor charges and another 25 on electronic monitoring. There are 144 people in the jail and 302 people on electronic monitoring for longer than 6 months on Class 3 felonies, and 100 people in the jail and 339 on house arrest who have served more than 6 months on Class 4 felonies – enough time that, were they given the minimum prison sentence on their charge, they would be released directly onto mandatory supervised release (essentially parole) and supervised at home by the Illinois Department of Corrections. Most Class 4 felonies that receive any incarceration time at all receive the minimum sentence of 1 year, and many of these cases can likely be quickly resolved so that individuals can return home.

- The State’s Attorney’s Office should carefully review cases eligible for diversion that were initiated during the pandemic and provide safe, efficient ways for those people to complete the diversion process, as they would have been before the pandemic. Most diversion programs in Cook County rely on in-person interviews with court personnel in order to intake new defendants into the program. Unsurprisingly, this effort was halted during the pandemic. However, these diversion programs are an important way to both administer justice fairly and to keep court caseloads reasonable and manageable by diverting lower-level, less serious cases. Unfortunately, it is not the case that no one in the jail or on electronic monitoring is charged with a low-level, divertable case. There are still over 200 people in the jail held on only narcotics charges.

- Stakeholders should move most of the current electronic monitoring population off the program and release them with non-custodial conditions. Two-thirds, or 66% of people on EM have been in the Sheriff’s custody for at least six months at this point. Violations of program rules generally lead to reincarceration; this means that most of the people who have been on the program for months have done so without breaking any rules. There is little reason to think that a person who has successfully followed the extremely strict rules of house arrest for months on end would immediately pose a threat to their community if released. Electronic monitoring is incredibly damaging to participants’ lives and livelihoods; removing the current group of people from electronic monitoring could also provide an opportunity for individuals charged with more serious offenses to be released from the jail and monitored, should a judge believe it is necessary.

II. Failure to Appropriately Implement Illinois Law and Court Rules regarding the Setting of Bail Strands People in Jail

Perhaps more concerning than the slowdown of case resolutions is the lack of clear legal rationale for why many of these long-term detainees are incarcerated. Over 90% of people housed in Cook County Jail are there pretrial, and thus are presumed innocent until proven guilty. The presumption of innocence is more than a theoretical value; it is an important constitutional protection that prevents harm.

Even in the most serious or violent cases, a substantial number of people who are charged with crimes will ultimately be released from jail and the court system without a conviction – about 33% of people charged with murder or attempted murder were found not guilty on all charges or had all charges dismissed against them between 2015 and 2020. It’s important to think of this number as a minimum, rather than a maximum, number of people who are possibly not guilty of the serious crimes of which they are accused. Chicago leads the nation in overturned convictions, where convictions for murder and other crimes have been proven to be based on faulty evidence decades after the case was first charged – when those faulty convictions happened, the victims of wrongful convictions were viewed as people who had be proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Currently, Cook County operates on a money bail system, where individuals pay a certain amount of money and then are released to await their trial and follow any conditions the court may set, at home. Monetary bail is intended to be used to facilitate release of people pretrial, not as a method to jail them. Nonetheless, about half of the people who have been held for over one year in Cook County Jail are held on Money Bonds they cannot post. These bonds vary widely – the lowest amount set for someone who has been held for a year or more is $500; the highest is over $1 million.

On average, those 181 innocent people who had waited over three years for their cases to resolve from 2015 to 2020 most likely spent those years in custody. The State’s Attorney’s data does not provide an exact count of the custody status of each individual charged with murder, and because these data are anonymized, it is not possible to be certain whether these people were in the jail pretrial in the jail. However, the number of murder cases currently pending in the Cook County Courts is comparable to the number of people awaiting trial on murder, and stakeholders interviewed generally agree that it is very rare for a person charged with murder or attempted murder to be released pretrial.

In all of these cases, money bonds have not been reviewed or lowered, which is in direct violation of Chief Judge Timothy Evans’ General Order 18.8A. This order requires Cook County Judges who impose money bonds to make a finding that “the defendant has the present ability to pay the amount necessary to secure his or her release on bail.” Obviously, if a person has stayed in jail on an unposted money bond for over a year, with multiple appearances before a judge where they have manifestly been unable not secured the money necessary to be released, they do not have the “present ability” to pay the bond, and General Order 18.8A requires that the bond be lowered. Judges, however, have not followed this rule.

Chief Judge Evans, State’s Attorney Foxx, Public Defender Campanelli, and Sheriff Dart have all agreed that unpaid money bond is an inappropriate and unfair way to hold people in custody. Despite this broad consensus, however, the offices that these stakeholders oversee do not always comply with Court Orders and policy. As reported by Chicago Appleseed in May, Assistant State’s Attorneys did not agree to release in between 70% and 80% of people with bond reduction motions brought during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic – despite efforts from State’s Attorney Foxx and her executive staff to work with other stakeholders to facilitate releases.

Today, the other half of the 2,259 people who have been in jail for over a year are held on “no bond,” meaning that a judge has decided that they may not be released on any conditions. No bail holds happen for a variety of reasons, but in most cases in Cook County, they are imposed without rigorously adhering to Illinois law.

Under current law (725 ILCS 110/5-6.1), the normal solution for judges in these situations would be simply to set a reasonable bail and release the defendant. If they believe that the person poses a danger to others, current law provides a hearing system where State’s Attorneys can present evidence that a certain person poses a serious danger if released. If the court finds that the person poses a real and present threat to someone’s safety, they can hold the person in jail without bail. This system is meant to make sure that long holds in jail are justified by a genuine threat to the community.

This procedure, however, is rarely followed in the Cook County Courts. Instead, judges hold people with no bail citing, simply, their inherent power (usually described as arising from Amendment VII of the Illinois Constitution and from 725 ILCS 5/110-4) to deny bail as part of administering their courtroom, and do not often follow any special procedure to protect a defendant’s due process rights. This method of holding people in custody is manifestly unjust, but was legally valid before December of 2019. Over a year ago, however, the First District Appellate Courts made clear – in a decision (People v. Gil, 2019 IL App (1st) 192419) that is binding precedent for the Cook County Courts – that judges must provide due process and provide a full and fair hearing before denying bail.

This decision, which happened over a year ago, has not been implemented in the Cook County Courts. The timing of People v. Gil has made its implementation more difficult – only three months after the ruling, the courts would largely shut down due to the pandemic, making major changes in procedure more difficult.

Nonetheless, it remains true that over 1,000 people are being held in jail without proper legal authority, away from their families, communities, jobs, and schools, and at high risk of death from COVID-19. Any effort to reduce the jail population, decrease length of stay, and honor the presumption of innocence must address this problem.

Every person in the jail is entitled to a detailed, rigorous hearing on whether they pose any danger to anyone if released pretrial. Each person must receive one, and those hearings must happen immediately.

Recommendations

To prevent people from being held in jail when it is not absolutely necessary, all Cook County has to do is simply follow the law. Judges must stop issuing detention orders in direct violation of binding appellate law. State’s Attorneys must take the legally required steps to request a “No Bail Hold,” rather than allowing illegal holds to happen in front of them without intervening, and defense attorneys, both public and private, should aggressively pursue appeals and legal re-hearings on these illegal detentions.

The decision to detain people who have not been convicted of a crime is influenced by the way crime is talked about and reported on in the public sphere – and by the way that court stakeholders are often blamed when a person awaiting trial is arrested for a new crime, although in reality, the rate of arrest of people awaiting trial for new violent crimes is very low, around 3%. That rate has remained steady despite major changes in bail procedures after General Order 18.8A; still, it remains common for judges and State’s Attorneys to be unfairly blamed when anyone released pretrial is arrested for another crime.

No system can entirely predict whether someone might commit a crime while released pretrial. We cannot expect our judges and State’s Attorneys to have a crystal ball that perfectly predicts the future, but we should expect them to follow the law and the constitution.

Over 30% of people whose cases were disposed of in Cook County between 2015 and 2020 had their cases dismissed or were found not guilty at trial. The best way to ensure public safety is to make detention decisions carefully, with longer, more detailed hearings, while keeping in mind that the vast majority of people appearing before the Court are not a danger to anyone while awaiting trial – that many will eventually be found not guilty or have their case dismissed – and that all arrested people have a constitutional guarantee of being presumed innocent.

III. Systemic Problems that Predate COVID-19 Make Many Cases Take Longer than Necessary to Reach Disposition

COVID-19 has created some new problems for the courts, but it has also exacerbated old ones. Chicago Appleseed has been gathering information from court stakeholders about inefficiencies and injustices in the pretrial system for many years. Below is a list of problems that have been voiced by multiple stakeholders in the Criminal Defense community, the State’s Attorney’s Office, and the judiciary that need to be improved to make Chicago’s criminal courts more efficient and fair.

- Cook County’s process of exchanging discovery is shockingly outdated. In the federal courts, and most other major state court systems, pieces of evidence are exchanged electronically as soon as they are received by the prosecutor. The Cook County Circuit Court continues to adhere to the outdated practice of physically exchanging paper copies of documents and CDs and DVDs of audio and video recordings only in court, not between court dates. As the amount of digital evidence in cases rapidly increases, this process is even more cumbersome than it was a decade ago. COVID-19 has further slowed this process, as attorneys often do not physically appear in court for status dates.

- Common, routine kinds of evidence regularly take months to obtain. Although every criminal case is different, there are a number of kinds of evidence that exist in most cases, including police radio recordings, 911 calls, and forensic testing results on firearms and drugs. Even State’s Attorneys report that their subpoenas to law enforcement agencies and other government agencies go unanswered for months at a time. It is common for attorneys to wait 4-6 months to receive basic police reports, videos, and recordings that constitute the bare bones of cases at trial.

- Judges rarely hold government agencies accountable when they fail to deliver documents in a timely fashion. Both the defense and State’s Attorneys have the ability to issue subpoenas for documents from any agency, public or private, that may have information relevant to the case. Subpoenas are a legally binding command from the court to produce a document by a certain date, or risk being held in contempt of court. However, judges almost never throw on these contempt charges – or even ask the record keepers to appear in court to explain why they did not respond to the subpoena. Without judicial enforcement, subpoenas cannot serve their intended purpose to compel the quick and complete cooperation of third parties so that criminal cases can resolve efficiently.

- Law enforcement officers fail to appear as required to testify at hearings and trials. All the criminal justice stakeholders Chicago Appleseed spoke to about court efficiency reported that subpoenaed Chicago Police Officers often do not appear in court when required. This causes particularly serious problems when evidentiary suppression hearings must be resolved before trial. Defense attorneys reported waiting, sometimes, for over a year for their subpoenas to be honored, with many separate subpoenas issued subsequently to require a certain officer’s appearance. Because of the volume of criminal cases, officers are often required to be in multiple courthouses on the same day, and CPD has rules about which dates should take priority. This remarkably common problem puts accused people and their lawyers in a catch-22: they cannot get the officer to come to court, but they also cannot demand trial, since – if they did – they would be waiving major constitutional arguments that might well resolve the case. Again, judges very rarely act to require officers to appear, or even to follow up on reasons for non-appearance.

- All court actors lack the support staff to efficiently practice criminal law in the modern, digital era. Like most county agencies, the Criminal Courts have experienced many budget cuts over the years. There are very few paralegals or investigators in either the State’s Attorney’s or the Public Defender’s offices. Now that criminal cases can include hundreds of hours of video footage from multiple sources, the need for support staff to assist in reviewing materials, locating and interviewing witnesses, and preparing legal arguments is all the more acute. Most Judges lack law clerks and other support staff to assist with research and decision making, and Judges spend most of their working hours on the bench, presiding over long court calls that consist mostly of status dates to exchange discovery or grant continuances.

- Unnecessarily frequent status dates prevent lawyers and judges from devoting appropriate time to their cases. In Cook County, by tradition and habit, cases are set for in-person status dates every 4-6 weeks, at which the prosecution, defense attorney, and defendant must all appear. Often, little of substance happens at these status dates (beside the updates on discovery noted above). However, the sheer volume of these status dates means that most “line attorneys” – the State’s Attorneys and Public Defenders directly responsible for cases – spend most or all of their workdays in court. This is an inefficient use of time for highly-trained and highly-paid lawyers. More importantly, these frequent mandatory status dates are extremely disruptive for defendants, who must secure time off work or school, childcare, and transportation for court dates where little or nothing happens. Other court systems, including the federal system, have fewer court status dates per case, but have more frequent electronic and verbal communication between the parties and with the judge if necessary. According to at least some lawyers and judges, reducing the number of status dates per case would greatly alleviate some of the case volume problems that cause delays in Cook County.

Recommendations

These problems are more systemic in nature than those mentioned in the first two Sections. Ultimately, however, many can be addressed by a combination of:

- Clearer court rules and better tracking and enforcement of their implementation. There is a particular need for rules regarding discovery exchange, how and when judges should enforce subpoenas against third parties, and how long cases should take to be disposed of, on average.

- Updated technology. The Criminal Courts are far behind the times on criminal justice technology. Our court system is among the largest in the world, and needs state-of-the-art tools to manage cases, exchange documents, and file legal motions.

- Increased support staff and better uses of attorney capacity. Frequent status dates sap most of the time that Defense and State’s Attorneys should be spending on preparing cases. This problem is compounded by a lack of non-lawyer support staff to find and interview witnesses, follow up on document requests, and research legal arguments.

The last two of these recommendations require funding, which is, of course, in short supply in many Cook County Departments. However, Cook County’s focus on decarceration since 2014 has shrunk the jail population by almost half – and, as described above, yet more decarceration can still be done without any impact on public safety. Jail is oppressive and harmful to humans’ wellbeing. It is also incredibly expensive, and housing accused people who have not been found to be a danger to others in the jail spends money that could be better spent on modernizing and improving our criminal justice procedures.

Notes: This analysis was completed by Sarah Staudt, Senior Policy Analyst & Staff Attorney for Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts and the Chicago Council of Lawyers. The underlying data comes from jail and electronic monitoring rosters that provide a “snapshot” of the Jail and EM population on 12/31/20. They were obtained through a monthly FOIA request from the Cook County Sheriff’s Office. Detention lengths were calculated by a simple count of months from admission date for each person and counted only pre-trial detainees. Analysis of Court Statistics was obtained from the “dispositions” table from the States Attorney of Cook County’s Open Data portal, available at https://datacatalog.cookcountyil.gov/browse?category=Courts, and dates from the the update of that data provided on October 29, 2020.